Redux with existing Application

This parallels the first part of this tutorial, where we’ll take a plain React app and add Redux to it one piece at a time.

Or, keep reading! The tutorial below covers everything in the video and then some.

Should You Use Redux?

It’s especially valid, in 2019, to wonder… should you still use Redux? Is there something better out now, with Hooks or Context or some other library?

The short answer: Even with plenty of alternatives, Redux is not dead yet. But whether or not it makes sense for your app… well, it depends.

Super simple? Only a few bits of state in one or two places? Local component state will probably be great. You can do that with classes, Hooks, or both.

A bit more complex, with a few “global” things that need to be shared across the app? The Context API might be perfect for you.

Lots of global state, with interactions between disconnected parts of the app? Or a big app that will only get bigger over time? Give Redux a try.

You can always add Redux later, too. You don’t have to decide on Day 1. Start simple and add complexity when and where you need it.

Do You Know React Yet?

React can be used on its own without Redux. Redux is an add-on to React.

Even if you intend on using them both, I super strongly recommend learning pure React without Redux initially. Understand props, state, and one-way data flow, and learn to “think in React” before trying to learn Redux. Learning them both at the same time is a surefire recipe for confusion.

If you want a primer on React, I put together a 5-day free course that teaches all the basics:

Learn React by building a few simple apps over the next 5 days.Get Lesson 1

The Benefits of Redux

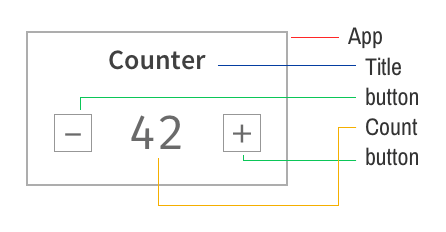

If you’ve used React for more than a few minutes, you probably know about props and one-way data flow. Data is passed down the component tree via props. Given a component like this:

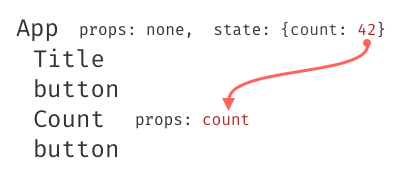

The count, stored in App’s state, would be passed down as a prop:

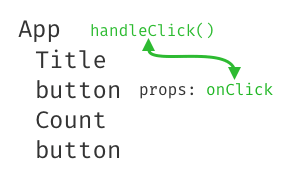

For data to come back up the tree, it needs to flow through a callback function, so that callback function must first be passed down to any components that want to call it to pass data up.

You can think of the data like electricity, connected by colored wires to the components that care about it. Data flows down and up through these wires, but the wires can’t be run through thin air – they have to be chained from one component to the next.

Passing Data Multiple Levels is a Pain

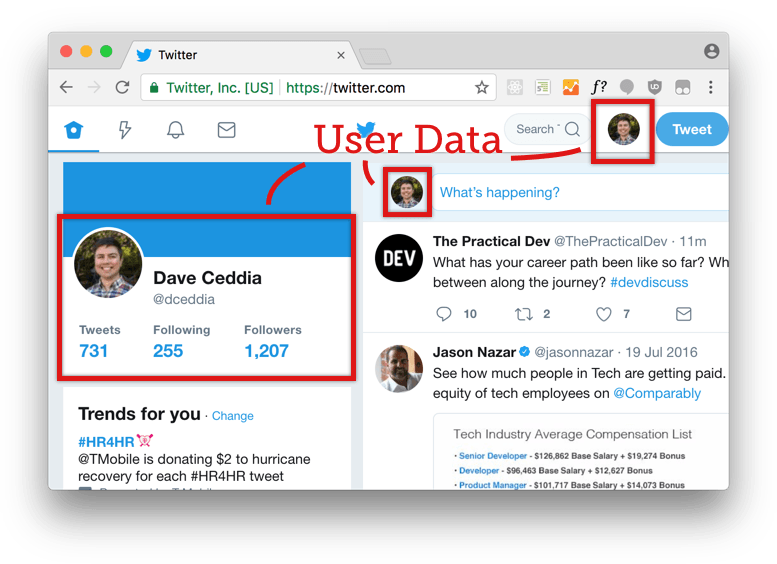

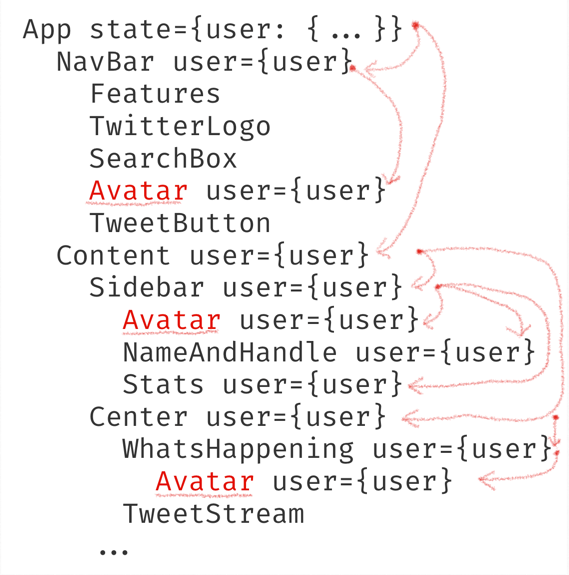

Sooner or later you run into a situation where a top-level container has some data, and a child 4+ levels down needs that data. Here’s an example from Twitter, with all the avatars highlighted:

Let’s pretend the top-level App component holds the user object in state. The user contains the current user’s avatar, handle, and other profile info.

In order to deliver the user data to all 3 Avatar components, the user needs to be woven through a bunch of intermediate components that don’t need the data.

Getting the data down there is like threading a needle through a mining expedition. Wait that doesn’t make any sense. Anyway, it’s a pain. Also known as “prop-drilling”.

More importantly, it’s not very good software design. Intermediate components are forced to accept and pass along props that they don’t care about. This means refactoring and reusing those components will be harder than it needs to be.

Wouldn’t it be nice if the components that didn’t need the data didn’t have to see it at all?

Redux is one way to solve this problem.

Passing Data Between Adjacent Components

If you have components that are siblings and need to share data, the way to do that in React is to pull that data up into a parent component and pass it down with props.

That can be cumbersome though. Redux can help by giving you one global “parent” where you can store the data, and then you can connect the sibling components to the data with React-Redux.

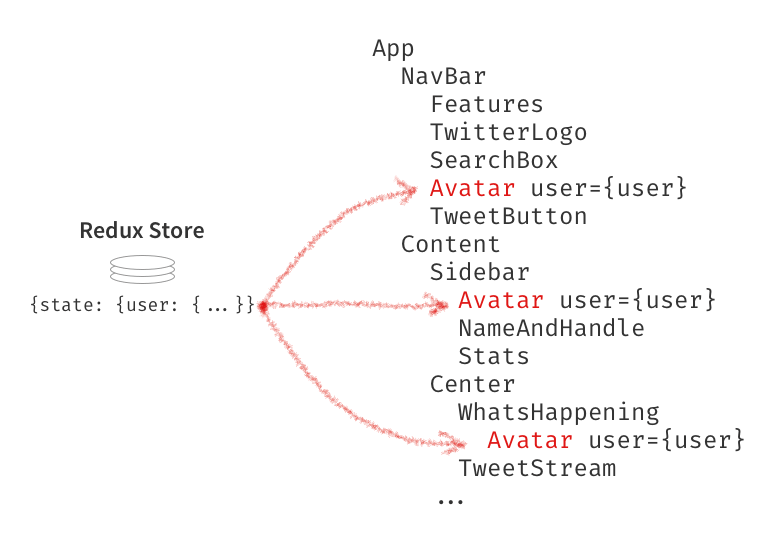

Use React-Redux to Connect Data to Any Component

Using the connect function that comes with react-redux, you can plug any component into Redux’s store and pull out the data it needs.

Redux does some other cool stuff too, like make debugging easier (Redux DevTools let you inspect every single state change), time-travel debugging (you can roll backstate changes and see how your app looked in the past), and it can make your code more maintainable in the long run. It’ll teach you more about functional programming too.

Built-in Redux Alternatives

If Redux seems like overkill for your situation, give these alternatives a look. They’re built right in to React.

Redux Alternative: The React Context API

Under the hood, React-Redux uses React’s built-in Context API to pass data around. If you want to, you can cut out the middleman and use Context directly. You’ll miss out on the nice features of Redux mentioned above, but if your app is simple and you want an easy way to pass data around, Context might be perfect.

Since you’re here, I’m gonna assume you want to learn Redux, and I won’t compare Redux to the Context API or the useContext and useReducer Hooks right here. You can learn more at those links.

If you want a deep dive on the Context API, watch my course React Context for State Management at egghead.

Another Alternative: Use the children Prop

children PropDepending on how you structure your app, you might be able to pass data to child components more directly using a combination of the children prop and other props as “slots”. You can effectively skip a few levels in the hierarchy if you arrange it right.

I have an article about this “slots” pattern and how to arrange your component treeto pass data more efficiently.

Learn Redux, Starting With Plain React

We’re going to take an incremental approach, starting with a plain React app with component state, adding parts of Redux piece-by-piece, and dealing with the errors along the way. Let’s call it “Error-Driven Development” :)

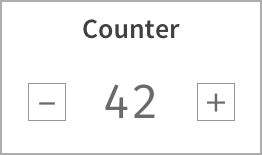

Here is a counter:

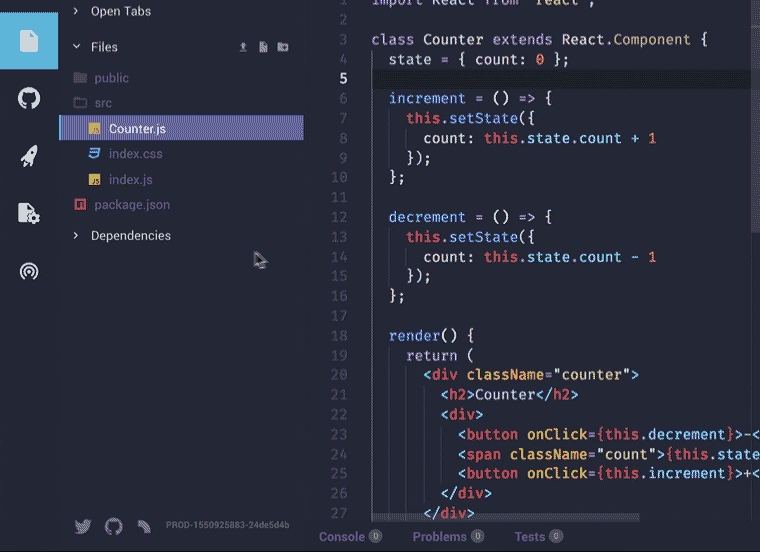

In this example, the Counter component holds the state, and the App surrounding it is a simple wrapper.Counter.js

As a quick review, here’s how this works:

The

countstate is stored in theCountercomponentWhen the user clicks “+”, the button’s

onClickhandler is called, which calls theincrementfunction.The

incrementfunction updates the state with the new count.Because state was changed, React re-renders the

Countercomponent (and its children), and the new counter value is displayed.

Follow Along!

The best way to actually learn this stuff is to try it! So here’s a CodeSandbox where you can follow along:

I highly recommend you keep the CodeSandbox in sync with the tutorial and actually type out the examples as you go along.

Add Redux To The React App

In CodeSandbox, expand the Dependencies section in the left pane, and click Add Dependency.

Search for redux, add it, then click Add Dependency again and search for react-redux and add it.

In a local project, you can install them with Yarn or NPM: npm install --save redux react-redux.

redux vs react-redux

redux gives you a store, and lets you keep state in it, and get state out, and respond when the state changes. But that’s all it does.

It’s actually react-redux that lets you connect pieces of the state to React components.

That’s right: redux knows nothing about React at all.

These libraries are like two peas in a pod, though. 99.999% of the time, when anyone mentions “Redux” in the context of React, they are referring to both of these libraries in tandem. So keep that in mind when you see Redux mentioned on StackOverflow, or Reddit, or elsewhere.

The redux library can be used outside of a React app too. It’ll work with Vue, Angular, and even backend Node/Express apps.

Redux Has One Global Store

We’re going to start by looking at just Redux by itself, and just one piece of it: the store.

We’ve talked about how Redux keeps the state of your app in a single store. And how you can extract parts of that state and plug it into your components as props.

You’ll often see the words “state” and “store” used interchangeably. Technically, the state is the data, and the store is where it’s kept.

So: as step 1 of our refactoring from plain React to Redux, we need to create a store to hold the state.

Create the Redux Store

Redux comes with a handy function that creates stores, and it’s called createStore. Logical enough, eh?

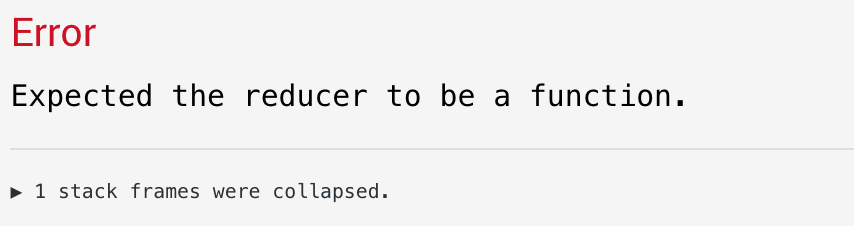

In index.js, let’s make a store. Import createStore and call it like so : index.js

This should fail with the error “Expected the reducer to be a function.”

The Store Needs a Reducer

So, here’s the thing about Redux: it’s not very smart.

You might expect that by creating a store, it would give your state a nice default value. Maybe an empty object, perhaps?

But no. No convention-over-configuration here.

Redux makes zero assumptions about the shape of your state. It could be an object, or a number, or a string, or whatever you need. It’s up to you!

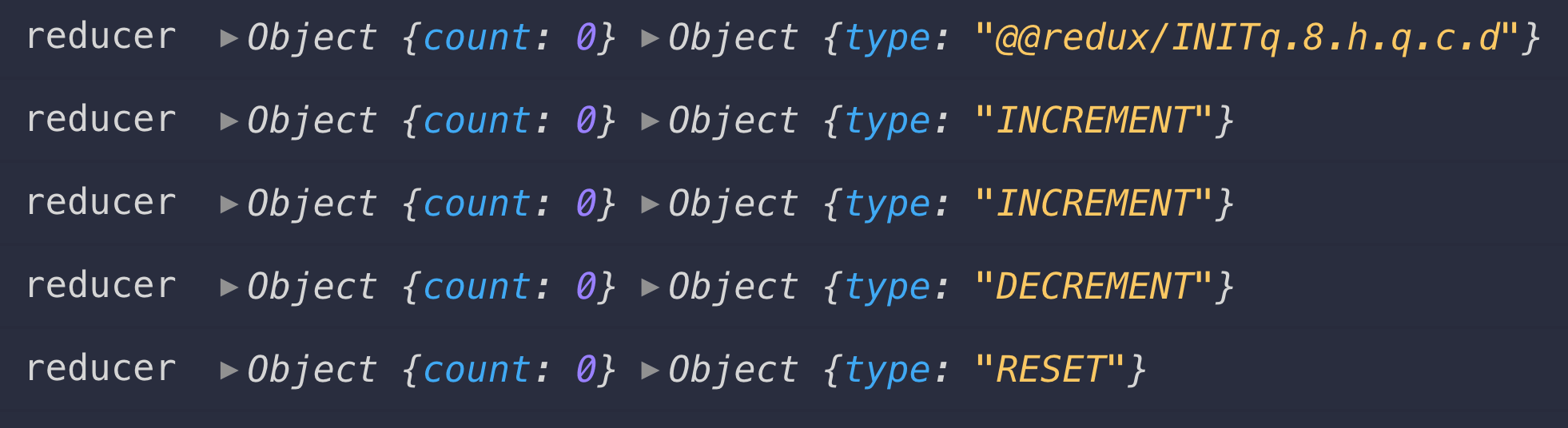

We have to provide a function that will return the state. That function is called a reducer (we’ll see why in a minute). So let’s make a really simple one, pass it into createStore, and see what happens:index.js

After you make this change, open up the console (in CodeSandbox, click the Console button at the bottom).

You should see a message logged there, something like this:

(the letters and numbers after INIT are randomized by Redux)

Notice how Redux called your reducer at the time you created the store. (To prove it: put a console.log immediately after the call to createStore and notice how it prints out after the reducer)

Also notice how Redux passed a state of undefined, and the action was an object with a type property.

We’ll talk more about actions in a minute. For now, let’s go over the reducer.

What Is a Redux Reducer?

The term “reducer” might seem a bit scary and foreign, but after this section I think you’ll come to agree that it is, as the saying goes, “just a function.”

Have you ever used the reduce function on an array?

Here’s how it works: You pass it a function, and it calls your function once for each element of the array, similar to how map works – you’re probably familiar with map from rendering lists of things in React.

Your function gets called with 2 arguments: the last iteration’s result, and the current array element. It combines the current item with the previous “total” result and returns the new total.

This will make more sense with an example:

The function you pass in to reduce could rightfully be called a “reducer”… because it reduces a whole array of items down to a single result.

Redux is basically a fancy version of Array’s reduce. Earlier, you saw how Redux reducers have this signature:

Meaning: it takes the current state, and an action, and returns the newState. Looks a lot like the signature of an Array.reduce reducer!

Redux reducers work just like the function you pass to Array.reduce! :) The thing they reduce is actions. They reduce a set of actions (over time) into a single state. The difference is that with Array’s reduce it happens all at once, and with Redux, it happens over the lifetime of your running app.

If you’re still super unsure, check out my guide to how Redux reducers work. Otherwise, let’s forge ahead.

Give the Reducer an Initial State

Remember that the reducer’s job is to take the current state and an action and return the new state.

It has another job, too: It should return the initial state the first time it’s called. This is sort of like “bootstrapping” your app. It’s gotta start somewhere, right?

The idiomatic way to do that is to define an initialState variable and use the ES6 default argument syntax to assign it to state.

Since we’re gonna be moving our Counter state into Redux, let’s set up its initial state right now. Inside the Counter component our state is represented as an object with a count, so we’ll mirror that same shape here.index.js

If you look at the console again, you’ll see it printed {count: 0} as the value for state. That’s what we want.

So that brings us to an important rule about reducers.

Important Rule of Reducers #1: Never return undefined from a reducer.

You always want your state to be defined. A defined state is a happy state. An undefined state is unhappy (and will likely break your app).

Dispatch Actions to Change the State

Yep, two new terms at once: we’re gonna “dispatch” some “actions.”

What is a Redux Action?

An action is Redux-speak for a plain object with a property called type. That’s pretty much it. Following those 2 rules, this is an action:

This is also an action:

Here’s another one:

Actions are very free-form things. As long as it’s an object with a type it’s fair game.

In order to keep things sane and maintainable, we Redux users usually give our actions types that are plain strings, and often uppercased, to signify that they’re meant to be constant values.

An action object describes a change you want to make (like “please increment the counter”) or an event that happenend (like “the request to the server failed with this error”).

Actions, despite their active-sounding name, are boring, inert objects. They don’t really do anything. Not on their own, anyway.

In order to make an action DO something, you need to dispatch it.

How Redux Dispatch Works

The store we created earlier has a built-in function called dispatch. Call it with an action, and Redux will call your reducer with that action (and then replace the state with whatever your reducer returned).

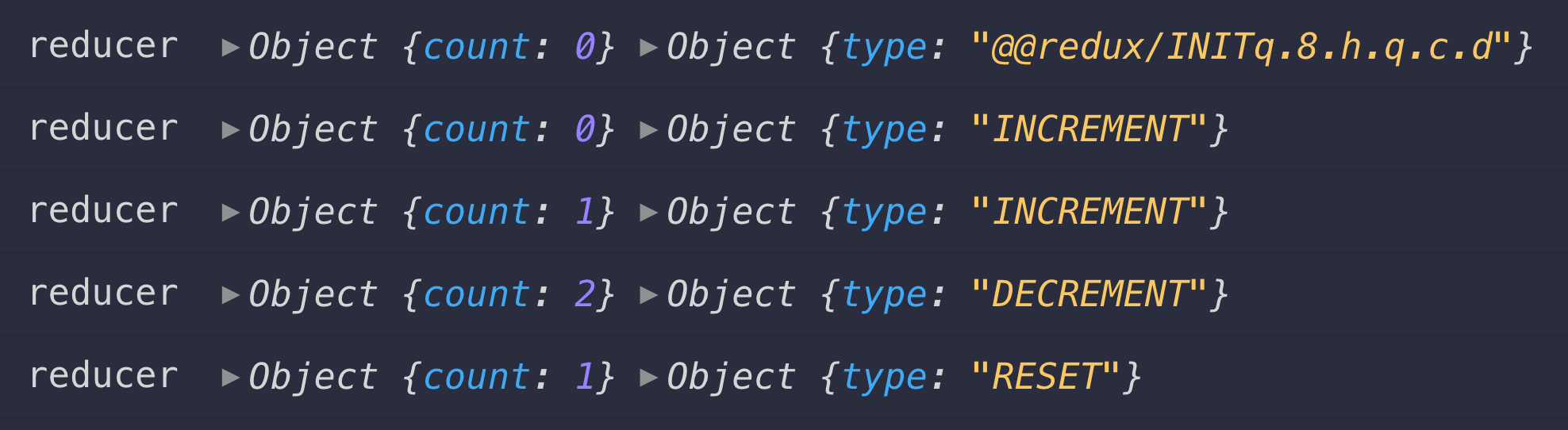

Let’s try it out with our store.index.js

Add those dispatch calls to your CodeSandbox and check the console.

Every call to dispatch results in a call to your reducer!

Also notice how the state is the same every time? {count: 0} never changes.

That’s because our reducer is not acting on those actions. That’s an easy fix though. Let’s do that now.

Handle Actions in the Redux Reducer

To make actions actually do something, we need to write some code in the reducer that will inspect the type of each action and update the state accordingly.

There are a few ways to do this.

You could make a fancy object where you look up a handler function by the action’s type…

Or you could write a bunch of if/else statements…

Or you could use a simple switch statement, which is what I’ll show below because it’s straightforward, and a very common way to do it.

Some people hate the switch though. If that’s you – please feel free to write your reducers however you want :)

Here’s how we’ll handle the actions : index.js

Try this out and take a look at the console.

Hey look at that! The count is changing!

We’re about ready to hook this up to React, but let’s talk about this reducer code for a second.

How to Keep Your Reducers Pure

Another rule about reducers is that they must be pure functions. This means that they can’t modify their arguments, and they can’t have side effects.

Reducer Rule #2: Reducers must be pure functions.

A “side effect” is any change to something outside the scope of the function. Don’t change variables outside the scope of the function, don’t call other functions that change things (like fetch, which affects the network and other systems), don’t dispatch actions, and so on.

Technically console.log is a side effect, but we’ll allow that one.

The most important thing is this: don’t modify the state argument.

This means you can’t do state.count = 0 or state.items.push(newItem) or state.count++, or any other kind of mutation – not to state itself, and not to any of the sub-properties of state.

Think of it like a game where the only thing you can do is return { ... }. It’s a fun game. Maddening at first. But you’ll get better at it with practice.

All These Rules…

Redux is built on the idea of immutability, because mutating global state is the road to ruin.

Have you ever tried keeping your state in a global object? It works great at first. Nice and easy. Everything can access the state because it’s always available, and making changes is simple.

And then the state starts changing in unpredictable ways and it becomes impossible to find the code that’s changing it.

Redux avoids these problems with some simple rules.

State is read-only, and actions are the only way to modify it.

Changes happen one way, and one way only: dispatch(action) -> reducer -> new state.

The reducer function must be “pure” – it cannot modify its arguments, and it can’t have side effects.

How to Use Redux with React

At this point we have a lovely little store with a reducer that knows how to update the state when it receives an action.

Now it’s time to hook up Redux to React.

To do that, the react-redux library comes with 2 things: a component called Provider, and a function called connect.

By wrapping the entire app with the Provider component, every component in the app tree will be able to access the Redux store if it wants to.

In index.js, import the Provider and wrap the contents of App with it. Pass the store as a prop.index.js

After this, Counter, and children of Counter, and children of their children, and so on – all of them can now access the Redux store.

But not automatically. We’ll need to use the connect function on our components to access the store.

How the React-Redux Provider Works

This Provider thing might seem like total magic. It is a little bit; it actually uses React’s Context feature under the hood.

Context is like a secret passageway connected to every component, and using connect opens the door to the passageway.

Imagine pouring syrup on a pile of pancakes, and how it manages to make its way into ALL the pancakes even though you only poured it on the top one. Providerdoes that for Redux.

Prepare the Counter Component for Redux

Right now the Counter has local state. We’re going to rip that out, in preparation to get the count as a prop from Redux.

Remove the state initialzation at the top and the setState calls inside increment and decrement. Then, replace this.state.count with this.props.count.Counter.js

This will leave increment and decrement empty. We’ll fill them in again soon.

You’ll also notice the count has disappeared – which it should, because nothing is passing a count prop to Counter yet.

Connect the Component to Redux

To get the count out of Redux, we first need to import the connect function at the top of Counter.js

Then we need to “connect” the Counter component to Redux at the bottom : Counter.js

Previously we were exporting the component itself. Now we’re wrapping it with this connect function call, so we’re exporting the connected Counter. As far as the rest of your app is concerned, this looks like a regular component.

And the count should reappear! Except it’s frozen until we reimplement increment/decrement.

How to Use React Redux connect

connectYou might notice the call looks little… weird. Why connect(mapStateToProps)(Counter) and not connect(mapStateToProps, Counter) or connect(Counter, mapStateToProps)? What’s that doing?

It’s written this way because connect is a higher-order function, which is a fancy way of saying it returns a function when you call it. And then calling that function with a component returns a new (wrapped) component.

Another name for this is a higher-order component (aka “HOC”). HOCs have gotten some bad press in the past, but it’s still quite a useful pattern, and connect is a good example of a useful one.

What connect does is hook into Redux, pull out the entire state, and pass it through the mapStateToProps function that you provide. This needs to be a custom function because only you know the “shape” of the state you’ve stored in Redux.

How mapStateToProps Works

connect passes the entire state to your mapStateToProps function as if to say, “Hey, tell me what you need out of this jumbled mess.”

The object you return from mapStateToProps gets fed into your component as props. The example above will pass state.count as the value of the countprop: the keys in the object become prop names, and their corresponding values become the props’ values. So you see, this function literally defines a mapping from state into props.

By the way – the name mapStateToProps is conventional, but it’s not special in any way. You can shorten it to mapState or call it whatever you want. As long as it takes the state object and returns an object full of props, you’re good.

Why not pass the whole state?

In the example above, our state is already in the right shape… and it seems like maybe mapDispatchToProps is unnecessary. If it essentially copies the argument (state) into an object that is identical to the state, what good is it?

In really small examples that might be all it does, but usually you’ll be picking out pieces of data the component needs from a larger collection of state.

And also, without the mapStateToProps function, connect won’t pass in any state data at all.

You could pass in all of the state, and let the component sort it out. That’s not a great habit to get into though, because the component will need to know the shape of the Redux state to pick out what it needs, and it’ll be harder to change that shape later, if you need.

Dispatch Redux Actions from a React Component

Now that our Counter is connected, we’ve got the count value. Now how can we dispatch actions to change the count?

Well, connect has your back: in addition to passing in the (mapped) state, it alsopasses in the dispatch function from the store!

To dispatch an action from inside the Counter, we can call this.props.dispatchwith an action.

Our reducer is already set up to handle the INCREMENT and DECREMENT actions, so let’s dispatch those from increment/decrement

And now we’re done. The buttons should work again.

Try this! Add a Reset Button

Here’s a little exercise to try: add a “Reset” button to the counter that dispatches the “RESET” action when clicked.

The reducer is already set up to handle this action, so you should only need to modify Counter.js.

Action Constants

In most Redux apps, you’ll see action constants used in place of plain strings. It’s an extra level of abstraction that can save you some time in the long run.

Action constants help avoid typos, and typos in action names can be a huge pain: no errors, no visible sign that anything is broken, and your actions don’t appear to be doing anything? Could be a typo.

Action constants are easy to write: store your action strings in variables.

A good place to put these is in an actions.js file (when your app is small, anyway)

Then you can import the action names, and use those instead of writing the strings

What is a Redux Action Creator?

Up til now we’ve been writing out action objects manually. Like heathens.

What if you had a function that would write them for you? No more mis-written actions!

I can tell you think this is crazy. How hard is it to write { type: INCREMENT }without messing up?

As your app grows larger, and you have more than 2 actions, and those actions start to get more complex – passing around more data than just a type – action creators can be helpful to have.

Like action constants, they’re not a requirement though. This is another layer of abstraction and if you don’t want to bother with it in your app, that’s fine.

I’ll explain what they are anyway, though. You can decide if you want to use them sometimes/always/never.

An action creator in Redux terms is a fancy term for function that returns an action object. That’s all it is :)

Here are two of them, returning familiar actions. These go nicely in actions.jsalongside the action constants, by the way.actions.js

I wrote them two different ways – as a function and as an arrow – to show that it doesn’t matter how you write them. Pick your fave and go with it.

You’ll notice that the function names are camelCase (well, they would be ifTheyWereLonger) while the action constants are UPPER_CASE_WITH_UNDERSCORES. That, too, is just a convention. Helps you know if you’re looking at an action creator function or an action constant. But feel free to name yours how you like. Redux doesn’t care.

Now… w hat do you do with an action creator? Import it and dispatch it, of course! Counter.js

The key thing is to remember to call the action creator()!

Don’t dispatch(increment) 🚫

Do dispatch(increment()) ✅

Remember that an action creator is a plain old function. Dispatch wants an action object, not a function.

Also: you will almost definitely mess this up and be very confused. At least once, probably many times. That’s normal. I still forget sometimes.

How to Use React Redux mapDispatchToProps

Now that you know what an action creator is, we can talk about one more level of abstraction. (I know. I KNOW. It’s optional though.)

You know how connect passes in a dispatch function? And you know how you get really tired of typing this.props.dispatch all the time and it bothers you how messy that looks? (go with me here)

By writing a mapDispatchToProps object (or function! but usually object) and passing it to connect when you wrap your component, you’ll receive those action creators as callable props. Here’s what I mean:Counter.js

This is nice because it saves you from having to call dispatch manually.

You can also write mapDispatch as a function, but the object covers probably 95% of what you need. You can read more about the functional mapDispatch form and why you probably don’t need it.

How to Fetch Data with Redux Thunk (Middleware)

Since reducers are supposed to be “pure,” we can’t do any API calls or dispatch actions from inside a reducer.

We also can’t do that stuff inside a plain action creator!

But what if we could make an action creator return a function that could do our work? Something like this:

Out of the box, Redux doesn’t support actions like this. Stock Redux only accepts plain objects as actions.

This is where redux-thunk comes in. It is a middleware, basically a plugin for Redux, that enables Redux to deal with actions like getUser(), above.

You can dispatch these “thunk actions” like any other action creator: dispatch(getUser()).

What’s a “thunk”?

A “thunk” is a (uncommon) name for a function that’s returned by another function.

In Redux terms, it’s an action creator that returns a function instead of a plain action object, like this:

If you wanna get technical, the function being returned is the “thunk”, and the one that returns it is the “action creator”. Usually I call the whole bundle a “thunk action.”

The function you return from your action creator will be passed 2 arguments: the dispatch function, and getState.

Most of the time you’ll only need dispatch, but sometimes you want to do something conditionally, based on some value in the Redux state. In that case, call getState() and you’ll have the entire state to read as needed.

How to Setup Redux Thunk

To install redux-thunk with NPM or Yarn, run npm install --save redux-thunk.

Then, in index.js (or wherever you create your store), import redux-thunk and apply it to the store with Redux’s applyMiddleware function:

Just make sure to wrap thunk in the applyMiddlware call or it won’t work. Don’t pass thunk directly.

An Example of Fetching Data with Redux

Let’s imagine you want to display a list of products. You’ve got a backend API that answers to GET /products, so you create this thunk action to do the fetching: productActions.js

The fetch("/products") part is what’s actually fetching the data. Then we have a few calls to dispatch before and after.

Dispatch the Action to Fetch the Data

To kick off the call and actually fetch the data, we need to dispatch the fetchProducts action.

Where should you do it?

If a particular component needs the data, the best place to kick off the fetch is usually right after that component mounts, in its componentDidMount lifecycle method.

Or, if you’re using Hooks, inside the useEffect hook is a good spot.

Sometimes you’re fetching truly global data that the whole app needs – think “user profile” or “i18n translations”. In those cases, dispatch the action right after you create the store, with store.dispatch, rather than waiting for a component to mount.

How to Name Your Redux Actions

Redux actions that fetch data usually come in triplets: BEGIN, SUCCESS, FAILURE. This isn’t a requirement, it’s only a convention.

This BEGIN/SUCCESS/FAILURE pattern is nice because it gives you hooks to keep track of what’s happening – say, by setting a “loading” flag true in response to the BEGIN action, and then false after SUCCESS or FAILURE.

And, as with pretty much everything else in Redux… this, too, is a convention you can feel free to ignore if you don’t you need it.

Before you start the API call, you dispatch the BEGIN action.

Then after the call succeeds, you dispatch SUCCESS with the data. If it failed instead, you dispatch FAILURE with the error.

Sometimes the last one is called ERROR instead. It doesn’t really matter what you call it, as long as you’re consistent about it.

Careful: Dispatching an ERROR action and handling a FAILURE will lead to no end of hair pulling as you trace through your code, realizing the action is dispatching correctly but the data is never updating. Learn from my mistakes :)

Here’s what those actions look like, along with action creators for them:productActions.js

We’ll write a reducer to save the products into the Redux store when it receives the FETCH_PRODUCTS_SUCCESS action. It’ll also set a loading flag to true when the fetch begins, and false when it finishes or fails.productReducer.js

Finally, we need to pass the products into a ProductList component that will display them, and also be responsible for kicking off the data fetching.ProductList.js

I’m referring to the data with state.products.<whatever> instead of just state.<whatever> because I’m making the assumption that you’ll probably have more than one reducer, each handling its own slice of state. To make this work, we can write a rootReducer.js file that pulls them all together:rootReducer.js

Then, when we create our store, we can pass this “root” reducer:index.js

Error Handling in Redux

The error handling here is pretty light, but the basic structure will be the same for most actions that make API calls. The general idea is:

Dispatch a FAILURE action when the call fails

Handle that FAILURE action in the reducer by setting some kind of flag and/or saving the error message.

Pass the error flag and the message (if you have one) into components that need to handle errors, and conditionally render the error however you see fit.

Can You Avoid the Double Render?

This is a really common concern. And yes, it will render more than once.

It will render in an empty state, then re-render in a loading state, and then re-render again with products to show. The horror! 3 renders! (you could get it down to 2 if you skip straight to the “loading” state)

You may be worried about unnecessary renders because of performance, but don’t be: single renders are very fast. If you’re working on an app where they are slow enough to notice, do some profiling and figure out why that’s the case.

Think of it this way: the app needs to show something when there are no products, or when they’re loading, or when there’s an error. You probably don’t want to just show a blank screen until the data is ready. This gives you an opportunity to make that user experience shine.

Last updated

Was this helpful?